Rapid population growth and the migration of rural youth to the urban areas show the importance of increasing agricultural production in Nigeria. But at the same time, a lack of mechanisation options has made it harder to raise yields and increase outputs. Off the back of a credit scheme initiated by the Central Bank of Nigeria, ATMANCorp Nigeria Ltd., created SecureFarmer, a block farming programme powered by a mobile app to deliver affordable technology to help farmers become more productive. The work of our agricultural processing company is already showing that helping them get access to credit, and boosting the productivity of smallholder farmers, are two of the crucial steps for achieving food security.

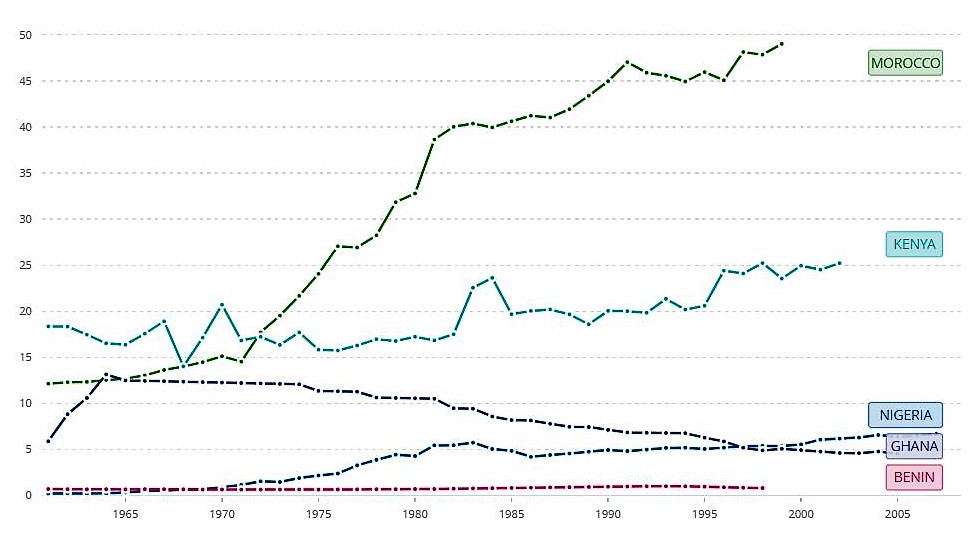

An increase in a country’s agricultural productivity levels can have an enormous contribution in terms food security and it can support its economic development. However, in Nigeria and in most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, such productivity gains have rarely been seen, and severe problems continue to plague the region. The discovery of oil in southeast Nigeria in the 1960’s led to a rapid urbanisation process, and many agricultural lands were left to fallow as a result. As such, agricultural production as a share of the country’s GDP decreased from 67% in the 1960s to 21% in 2017.[1] Concurrently, as this took place, Nigeria saw its population grow at rates of more than 2.5% per year. The national poverty rate increased as well – rising from 28.1% in 1980 to 40% in 2019.[2] Today, up to 80% of the population living in the rural areas is found below the poverty line. Farming remains the major source of employment in these areas, and manual cultivation methods are commonly practiced.[3] In fact, mechanisation in the agricultural sector is very low. Nigeria, for example, is one of the countries with the lowest number of tractors per 100 sq. km of arable land, in the world, as shown in the figure below.

A number of factors contribute to the low mechanisation rates seen in Nigeria’s agriculture. The high investment costs and the limited access to credit make it difficult for farmers to own tractors or other mechanised devices, especially for those whose average farm size is less than 2 hectares. This has a severe impact on the yields of staple crops, and the country lags behind the international averages. The national average yield for cassava, for instance, is 8.8 tonnes per hectare, while an average farmer in Thailand can harvest up to 23 tons per hectare.[5] Nigeria is required to import food to meet the country’s needs and agricultural imports cost more than €2 billion every year[6] – while at the same time only 47% of the country’s 87 million hectares of arable land is used.

With 70% of Nigerian farmers operating on small plots, only 4% use machineries or mechanised equipment.[6] Currently, Nigeria’s mechanisation rate stands at just 0.06 horsepower per hectare, well below FAO’s recommended rate of 1.5 horsepower per hectare.[7] Farmers in Nigeria have access to just 6.7 tractors for every 10,000 hectares of arable land[8].

In the past, the national government ran different initiatives that encouraged the use of machinery, but they had little impact. One of these programmes gave local governments access to tractors and, through federal funding, helped them provide different services to smallholder farmers. A comprehensive analysis showed that these programmes had a limited impact for several reasons. One of these was that the local governments did not have the staff and resources needed to maintain the equipment and effectively market their services.

ATMANCorp Nigeria LTD and mechanisation

In 2015, a scheme started by the Central Bank of Nigeria was launched to address these challenges. The Anchor Borrow Programme aimed to provide credit facilities to farmers by aggregating their produce and entering into a contract with an “anchor” – a guaranteed buyer who would pay a pre-negotiated price. The programme received immense praise from farmers and processors but did not yield the expected results due to a number of design issues. The selection of scattered farm sites for the programme made it difficult to monitor those who received loans from the government. As a result, the steps taken by farmers, input suppliers and service providers were not adequately known, and many inputs and crops were lost. Many farmers sold their crops and inputs without paying back their loans to the government. Additionally, the limited inclusion of mechanical and digital technologies reduced the use of advanced crop husbandry, and the farmers continued to cultivate using traditional methods. Largely as a result of these limitations, the programme is currently struggling to secure funding.[9]

As a potential “anchor” in the Anchor Borrower Programme, ATMANCorp Nigeria LTD realised the potential of the programme, but also saw the need to change it to make it sustainable. ATMANCorp is an integrated agricultural processing company specialising in the cassava value chain. The company started in the import and export business by shipping bulldozers, excavators, and other heavy equipment into Nigeria. Upon commencing operations, the management team observed the need for land clearing services, and it started providing these services to large farms in southwest Nigeria. The company later used that experience to acquire a 60-hectare farm just outside of Ibadan, in the Oyo State in 2009.oday, the farm has grown to over 720 hectares and processes cassava into three different food products, with a processing capacity of more than 50 tons of raw cassava per day.

ATMANCorp observed that in order to improve the Anchor Borrower Programme, a shift of key stakeholders from the public sector to the private sector was paramount. Executing the programme from the private sector would ensure it was market-led and that it would take farmer’s individual cultivation preferences into account. Under the new model, farmers are paid the market prices at the day they harvest, rather than a price negotiated one year in advance, as the government ABP required. In addition, each farmer can choose the services and inputs that he or she will receive, rather than a mandated set as dictated by the government programme. Furthermore, ATMANCorp discovered that farmers were willing to pay for crop information, improved inputs, and mechanical services, if they were partially financed by the company’s proceeds from the credit services they offer. Thus, the programme could help to increase yields and limit agricultural risks by providing farmers with the information they required. This all helped ATMANCorp develop the SecureFarmer programme and mobile application in 2018.

SecureFarmer

SecureFarmer is a “block farming” platform that aims to optimise the supply chains of agribusinesses that work with networks of smallholders to supply their raw materials. The platform reduces risk in a sector Nigerian banks are rarely motivated to join. SecureFarmer uses the concept of block farming, which involves farmer aggregation and the pooling of their resources, to help farmers access affordable inputs and services, whilst creating an economy of scale for service providers. Access to such services also assists farmers to reduce associated agricultural risks. Leveraging its experience in agriculture, farmer aggregation, and processing, ATMANCorp planned to increase the incomes of more than 3,000 farmers.

There are three main groups of stakeholders that ensure the viability and sustainability of the SecureFarmer model system. The first is made up by the smallholder farmers who produce at a location identified by SecureFarmer. Each SecureFarmer location is of at least 300 hectares, a size which can be accommodate up to 300 smallholder farmer plots. Farmers gain access to land, mechanical and digital technologies and high-quality inputs, and also a guaranteed purchaser for their products. The next stakeholder is the processor, or the “off-takers” or buyers, all of whom are longstanding agribusinesses looking to optimise their supply chains and receive scheduled deliveries and guaranteed quantities. The processors own or rent the land provided to the smallholder farmers under the SecureFarmer programme. The processors also act as the service providers, delivering inputs, training courses, transportation, mechanisation and logistics, and also provide management support. Under the programme, farmers are granted access to a range of timely mechanisation services to increase yields.

The final group are the financial institutions or donors who provide the capital, on credit, to the smallholder farmers. The SecureFarmer platform provides these institutions with up-to-date information on the health and the potential value of the farmers’ crops, thus limiting the risk to their capital. SecureFarmer also provides additional information, such as the expected harvesting dates and the expected yields, all of which requires the use of remote sensing technology and field agents. Additionally, via the deployment of drone-based technologies, artificial intelligence, and multispectral data analysis, SecureFarmer provides and crop advice to farmers.

SecureFarmer harnesses digital and mechanical agricultural technologies designed for Africa and works to create value for farmers within the community. Tractors used at the SecureFarmer properties are outfitted with HelloTractor GPS monitoring devices (see box).

Hello Tractor is an award winning diversified ag-tech company focused on improving food and income security throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Resource poor farmers often face labor constraints that result in under cultivation, late planting, and lost income. Hello Tractor facilitates convenient and affordable tractor services to these farmers while providing additional income by turning tractor’s into Smart Tractors. For Smart Tractor owners, our platform provides remote tracking of assets, preventing fraud and machine misuse, through virtual Smart Tractor monitoring. Hello Tractor is an award winning diversified ag-tech company focused on improving food and income security throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Resource poor farmers often face labor constraints that result in under cultivation, late planting, and lost income. Hello Tractor facilitates convenient and affordable tractor services to these farmers while providing additional income by turning tractor’s into Smart Tractors. For Smart Tractor owners, our platform provides remote tracking of assets, preventing fraud and machine misuse, through virtual Smart Tractor monitoring. |

HelloTractor services deliver critical information to tractor owners and operators, reducing the operation costs. These devices track and confirm that the land preparation activities have taken place, without requiring the farmer to be onsite to monitor all operations. The tractors’ tasks are stored in the SecureFarmer’s databases, and a task completion message is sent to farmers via SMS or e-mail. Remote sensing imagery and analysis is also available, and the data is cost effective due to the aggregation of multiple farm sites. Typically deploying this technology for a one-hectare site would be too costly, but covering more than 300 hectares makes it cost effective.

By providing data driven decision-making tools with the deployment of drone-based technologies, multispectral data analysis and artificial intelligence, SecureFarmer can also offer and crop advice to the farmers. It shares such advice through its mobile application, reaching farmers who own smart phones directly (or also indirectly via the local extension agents). SecureFarmer is able to monitor the use of inputs provided on credit via geo-referenced imagery of a farmer’s plot; and ensure that the funds provided for buying and applying agrochemicals are properly invested in the farm, thus enabling farmers to pay back the inputs and services they received.

As the population of Nigeria continues to grow, significant financial and technical support is needed to help farmers increase their yields – and to help them respond for the demand for more food. The SecureFarmer platform will be deployed by ATMANCorp Nigeria Ltd in 2020 with a grant support of the Policy Center for the New South reaching 300 farmers in 2020 and will then expand and reach 3,000 farmers in the near future. We will continue delivering affordable technology, making Nigerian farmers more productive.

Seyi Oyenuga

Executive Director and Head of Agriculture Division

ATMANCorp Nigeria LTD

Email: seyi@atmancorporation.com

www.atmancorporation.com

www.securefarmer.com

References

[1] Tolulope Odetola and Chinonso Etumnu (2013) Contribution of Agriculture to Economic Growth in Nigeria. Paper presented at the 18th Annual Conference of the African Econometric Society (AES) Accra, Ghana on 22nd and 23rd July, 2013 http://www.aaawe.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Tolulope_paper_mod.pdf

[2] Natural Bureau of Statistics 2019 Poverty and Inequality in Nigeria

[3] World Bank Report: Nigeria Agriculture and Rural Poverty https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/19324/783640ESW0P1430Box0385290B00PUBLIC0.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[4] Role of Cassava in Thailand: http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=748&print=1

[5] PWC: Unlocking Nigeria’s Agriculture Exports https://www.pwc.com/ng/en/assets/pdf/unlocking-ngr-agric-export.pdf

[6] IFPRI: Overview of the Evolution of Agricultural Mechanisation in Nigeria http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/132790/filename/133002.pdf

[7] World Bank: Agribusiness Indicators http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/909651468193779954/pdf/949650WP0P12860Country0Study0R20ST.pdf

[8] World Bank: FAO https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.TRAC.ZS?locations=NG

[9] This Day https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2020/03/02/cbn-and-the-anchor-borrowers-programme/