Harmonising drone regulations in Africa will ease the movement of drone operators across countries facilitating the contribution of the drone industry to the economic and social development of the continent as envisioned by the African Union. Using the case of Benin and Senegal, the present study shows this harmonisation is possible and will just require reconciling some dissimilarities between the regulations.

Since their introduction into the civilian sector, Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPASs) communally called drones have found practical applications in many fields. While their use has seen an exponential growth in the past few years, largely as a result of the many advantages they offer, they still present potential risks to the public – especially if the users do not follow airspace regulations. Several civil aviation authorities, for example, have raised the possibility of collisions between aircrafts and Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA). This has led to the development and adoption of regulations related to RPAS in many African countries, in some cases even amending the local aviation regulations with relatively stricter norms. For example, in 2015 Madagascar adopted an initial decision that banned the use of drones in their airspace and two years later its civil aviation authority issued newer rules. In the same dynamic, various African countries have adopted specific regulations for RPASs. This is the case of Cote d’Ivoire in 2017, Benin, and Senegal in 2018, Burkina Faso in 2019. However, the regulations are not harmonised. There are some dissimilarities between the different regulations, making it difficult for pilots in different countries to refer to common rules and share skills. This could dampen the expected impact of the drone industry on the continent’s economic development. The free movement of drone operators could benefit enormously from a process aimed at harmonising drone regulations as it is happening in the European Union.

This harmonisation process requires an extensive analysis of the gaps and differences. The purpose of this blogpost is precisely to compare RPAS regulations in West Africa by using two countries as a case study: Benin and Senegal.

The complete analysis, commissioned by the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation ACP-EU (CTA), can be downloaded here.

The official texts governing the use of drones in Benin and Senegal were taken from the websites of Global Partners for Benin, Senegal’s National Agency for Civil Aviation and Meteorology , and the Wikipedia-like www.droneregulations.info portal. The analysis of the regulations focused on aspects such as their overall structure, the categorisation of RPASs, the uses which are authorised, the authorisation conditions, the instructions related to the training of remote pilots, and other related data. The similarities and differences have been highlighted in order to make recommendations.

Differences and similarities

The regulations related to the use of RPAS were adopted in 2018 in both Benin and Senegal. In Benin, the regulation considers two documents: the “Règlementation technique relative à l’utilisation des aéronefs piloté à distance” adopted on September 17, 2018, and the Application Procedures published separately. For Senegal, the reference text is “l’Annexe 5 au Règlement Aéronautique du Sénégal N°06 portant sur les systèmes d’aéronefs télépilotés” adopted on November 5, 2018. The two basic texts are very similar, with sections that go from the preliminary previsions to the requirements and skills for licenses. These include the provisions on the operation of RPAS in general, those covering the commercial operation of RPAS, RPAS operations for leisure purposes and the safety requirements for RPAS operations.

Going through the different chapters, a comparative analysis revealed a lot of similarities, but also some differences. The classification of RPAs is identical in the two national regulations, distinguishing three categories according to the weight of the RPA and three different types of use. However, whatever the type of RPASs, the legal age to be eligible to use one is fixed at 18 in Benin (chapter 2.2), while in Senegal it is possible to use an RPAS at a younger age, provided that the aircraft is declared in the name of the legal guardian (chapter 2.2).

Owners of an RPAS might be required to possess a certificate before operating it. The Beninese regulations require a certificate only for commercial uses, while in Senegal the regulations systematise the type of certificate to be held by any operator. Indeed, the Senegalese regulations impose a certificate for class 3 (drone of 25 kg and more) whatever the type of use (chapter 3.1). For class 1 and 2 only operating authorisations of limited duration are granted to operators who request it (chapter 2.1). To obtain this certificate, in addition to the provisions common to both regulations, that of Benin requires the operator to hold proof of ownership of the RPAS and an import authorisation for RPASs weighing more than 25 kg. The authorities in Benin are more lenient when it comes to filing the certification request. Indeed, this deadline is fixed at 30 days (Chapter 4.2), while in Senegal (Chapter 4.2) “anyone applying for a license must submit their request for a first delivery at least three months before the date of start of planned operations”. In addition, a license is valid for 24 months in Benin, which is twice as long as in Senegal. When the license expires, the operator must renew it. The renewal period and processes are clearly specified in the Senegalese regulations (Chapter 4.4-b) which is not the case for the ones in Benin. Caution would recommend starting the renewal procedure at least one month before the license expires, considering that the period for obtaining the license in Benin takes 30 days.

Authorisations are required to use the drones in the national airspace in both countries, and each regulation specifies the conditions under which such an authorisation can be requested. In addition to several common elements and conditions, an authorization from the Ministry of the Interior and Public Security must also be attached to the request in Benin (chapter 3.6-f-3). In general, for cross-border operations, the drone operator needs approval of the civil aviation authorities of the countries concerned. However, in Senegal, the use of an RPAS for international navigation taking off from or landing in Senegal is prohibited, while in Benin it is allowed (chapter 3.2-c), provided that the request is submitted with a specific form (R2-OPS-FOR-06) and with the authorisation of the civil aviation authority.

The operations which are prohibited are identical in the two countries: the maximum height allowed is 300 ft (i.e. 91.5m). But while this holds for all types and use categories in Senegal, Beninese regulations allow RPASs used for leisure purposes to go up to 400 ft (or 122 m) above the ground (Chapter 3.4-a).

The specific places where an RPA can be flown are also considered, regulating operations in the vicinity of aerodromes or in other areas. In Senegal, an operator cannot be found at less than 10 km from an aerodrome without a formal authorisation from the authority in charge of operating the aerodrome (chapter 3.12-1). The Beninese regulations, in contrast, provide some nuances: this limit is fixed at 10 km outside of the reference point for aerodromes with codes C, D, E, and F (chapter 3.11-1), and at 7 km for aerodromes with code A and B (chapter 3.11-2).

Naturally, accidents can occur during RPAS operations, with possible consequences or damages to third parties. This is why, as in most other countries, the two regulations specify the need to have insurance covering any possible damage to third parties. Both countries require a compulsory report in the event of an accident involving an RPAS, and this must be filed within 48 hours in Benin (Chapter 3.5) and 72 hours in Senegal (Chapter 3.6).

In order to carry out RPAS commercial exploitations, the personnel required in the two regulations is the same (chapter 4.7). However, staff requirements vary slightly from one country to the other. For example, in Benin, the visual observer must hold a restricted aeronautical radiotelephone license, in accordance with the Procedure for the Application of Technical Regulations relating to the use of remotely piloted aircraft in its chapter 4.7- 1.iii.

To use an RPA, the remote pilot must necessarily undergo theoretical and practical training in both countries. The training programme differs very little in the two countries. In both cases this training must be provided by organisations that have been registered and approved, but the exams are supposed to be organised by the civil aviation authority, which issues the licenses. In practice, there are not many training centres in Benin nor in Senegal, and when they exist, these are not easily accessible to drone users.

Next steps

We can see that the documents regulating to the use of drones in Senegal and Benin share a lot of similarities, but they also have minor differences. Given the similarities, we believe that harmonising them can be done easily, and this scan have a very positive impact on the mobility of drone pilots between the two countries. The mobility of drones’ operators in Africa can benefit from a harmonisation process that also covers other countries, as recommended by several experts, and as environed in the European Union.

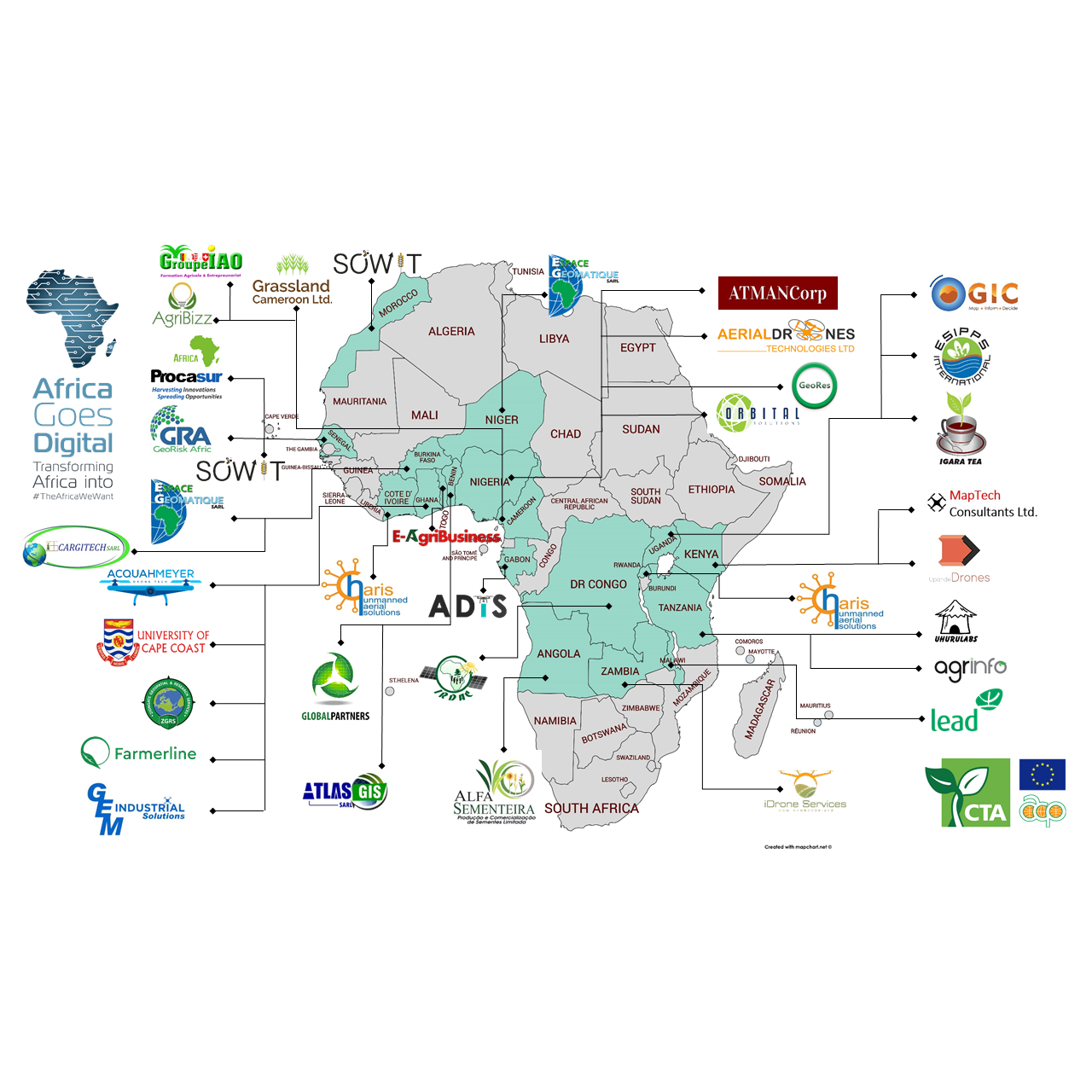

In order to address the lack of training centres in Africa, Global Partners has initiated the “Drone Academy Program”. Thanks to the support of CTA, Global Partners has adapted the course on Unmanned Aerial Systems developed by the School of Aviation at Eastern Kentucky University (U.S) to the RPAS regulations in Africa. The pilot phase being conducted in Benin and Senegal has successfully trained more than 200 drone operators. The program will expand to many other African countries and drone operators, members of the Africa Goes Digital network.

The authors invite drone operators to check the accuracy of the information provided on the www.droneregulatons.info portal and to contribute to its updating if necessary. This shared resource can assist regulators in being aware of the status of drone governance in other countries.

About the authors:

Dr Ismail Lawani

Research and Innovation Adviser at Global Partners

Associate Professor at the University of Abomey-Calavi

Email: ismaillawani@gmail.com

Elsa Lesly Guirendou Mourambou

Position: CEO of ISEL

Email: elsalelsy@isel.store

Dr Abdelaziz Lawani

Founder of Global Partners SARL

Assistant professor at Eastern Kentucky University

Email: abdelawani@gmail.com

www.gblpartner.com

Global Partners SARL